Discussion - Behaviour

Social behaviour

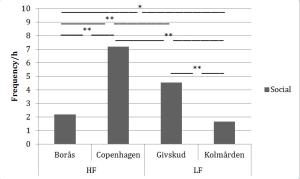

Social behaviour was more frequent for lions kept on HF feeding compared to those kept on LF feeding.

However, both feeding regimes showed significant differences in social interactions within themselves (see Figure 1). Sociality among lions depends primarily on relatedness and age of the pride members (Schaller 1972, Packer & Pusey 1997, Packer et al. 2001). Social play and stalking are play behaviours that lion cubs frequently engage in (...) (Schaller 1972). Therefore, the presence of cubs skews the data for the HF prides towards a higher frequency of social interactions.

Therefore, the frequency of social behaviours did not primarily depend on feeding regime, but seemed to correspond to group composition (...) and average age of the pride.

Agonistic behaviour

Lions on HF feeding engaged more frequently in agonistic behaviours compared to lions on LF feeding.

Feeding is reportedly the ‘most common context for aggressive competition in lions’ (Packer et al. 2001) and therefore it seems likely that alliances, if not hierarchies, are maintained or established during communal feeding.

If social discrepancies are solved during communal feeding, lions on HF feeding, who were fed with separate pieces of meat, have to resolve their social tensions in between feeding time. This may lead to the higher level of agonistic interactions inbetween feedings. For some social living species, such as bushdogs, communal carcass feeding is considered to benefit the group cohesion, which indicates that lions, too, might profit from whole carcass feeding (Macdonald 1996)

Marking behaviour

Marking behaviours were significantly more frequent for lions in HF zoos than for lions in LF zoos.

Marking behaviour is often conducted in certain places along the edges of a territory (Schaller 1972, Smith et al. 1989). Schaller (1972) observed that, when one individual puts its mark, other lions tend to imitate the behaviour. Considering that the edges of the territory in wild-living lions are equal to the edges of the enclosure of captive lions, marking spots in the big enclosures of LF zoos were mostly not visible from my observation position.

What is more, Lehmann et al. (2008) observed that (...) two lion males spent more time separated from the females. The two lion brothers in Kolmården behaved similarly and were often out of sight. As marking behaviour is mainly performed by males, occurs communally and along the edges of the exhibit, the marking frequencies of the lions in Kolmården (and to a similar extent also Givskud) were more frequent than I was able to record. Therefore, this behaviour category was confounded by lack of visibility as the LF prides were housed in disproportionally bigger exhibits than the HF prides.

Exploratory behaviour

Exploratory behaviours were significantly more frequent for lions on HF feeding than for lions on LF feeding.

This seems counterintuitive, as a longer period between feedings(...) should lead to elevated exploration (Horat et al. 1994, Hansen et al. 2015). Indeed, foraging behaviour has been shown to increase with progressive food deprivation, but due to lowered metabolic rate and exhaustion, fatigue will at some point become more prevalent (Scharf 2016). If the lions on LF feeding were less explorative due to exhaustion, the frequencies of exploration during the consecutive fasting days should first increase and then drop. However, this is not the case.

So why was exploration high for lions on HF feeding? Leyhausen & Tonkin (1979) found that exploratory behaviour in small cats is dependent on hunger: less food given during feeding time causes more exploration. There is the possibility that the smaller amount of food given to lions on HF feeding does not lead to complete satiation. Elliott et al. (1977) found that the (...) amount of food consumed, correlated significantly with the time delay until the next active search for prey was initiated. Accordingly, it is possible that lions on HF feeding did not reach a level of satiation (...).

Maintenance behaviours

Lions on LF feeding engaged more frequently in maintenance behaviours than lions on HF feeding.

However, frequencies of maintenance behaviour were more similar for lions on different feeding regimes than for lions on the same feeding regime. This suggests that the feeding regime has no systematic impact on the average frequency of maintenance behaviour in captive lions.

Responsible for this page:

Director of undergraduate studies Biology

Last updated:

05/20/17